Living Near Power Lines

Back in 2010, when Dana Saxon decided that she wanted to trace her family's lineage, her expectations were low. "I thought, for people who survived slavery, there'd be little public information," she says. What happened next "blew her mind"–and led to the creation of Ancestors Unknown, an international nonprofit that is bringing the past to the most impressionable among us: young students.

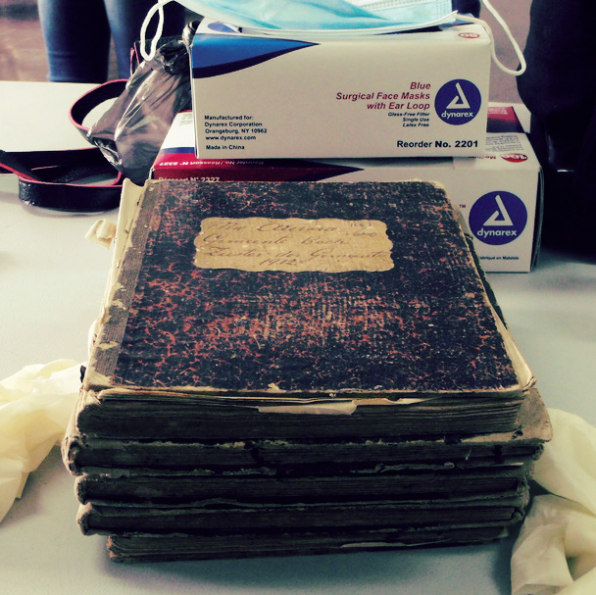

Saxon discovered that public archives had not completely ignored the existence of the enslaved, who legally were considered the same as property. While putting together the puzzle of her family's past, she had an epiphany: "There were so many ancestors waiting to be discovered, waiting to be appreciated for what they did to help get us to where we are today," she says. Knowing that most school curriculums do not include the names and contributions of people from the African Diaspora, she "wanted to find a way to help young people place themselves and their ancestors in the larger context of history."

But before Saxon could change how people learn, she had to return to school. So she quit her job as a social network director at a mentoring organization, packed up her Brooklyn apartment and headed to University of Amsterdam to earn her master's degree in sociology, with a focus on migration and ethnic studies. "I wanted concrete research to tie in the significance of knowledge of family history with the development of positive identity in black populations," she says.

After graduating, she went to work creating Ancestors Unknown, which offers a two-part curriculum that can be used in high schools around the world. One part consists of genealogy research training, and the second centers on history. "It focuses on the untold stories of the African Diaspora–to open people's minds that our history is there, it hasn't been erased," she says.

Saxon launched with two pilot programs in 2013. One was in Suriname, where she enlisted local educators and historians to host workshops for youth participants. The other is in Charleston, South Carolina, where a high school English teacher used the curriculum to boost her students' enthusiasm for learning, while showing them that they were capable of researching and writing about something that mattered to their own lives.

The programs were successful, in large part because they taught Saxon a much-needed lesson: She needed to figure out how to monetize her offerings to keep the nonprofit moving forward. The first step: go online. "Now instead of me having to come and present it, you can access and license it through our website," she says about the revised curriculum, which can be optioned for six-month sessions or a full academic year. "And because it is comprehensive, you don't have to be an historian or genealogist to teach it."

The second step: find supporters. Though she was able to launch thanks to a crowdfunding campaign, Saxon needed more–and more stable–financial resources. That is starting to arrive in the form of sponsor support from established companies including Barnes & Nobles and the Gilder-Lehrman Foundation. Most recently, Ancestry.org donated free access to all of the schools using her curriculum.

In just a year, Saxon and Ancestors Unknown have already changed lives. When she went for a follow-up visit in Charleston, she asked students, "Why is it important to be remembered?" and listened as the kids excitedly explained that after learning about their ancestors' achievements, they plan on living lives that will be remembered by their descendants. One student, on the verge of suspension, was more engaged than he had been all school year, peppering her with questions and making the connection between history, migration patterns, and his own future.

Though Saxon's initial goal was to educate young people, she will not be satisfied until she changes the very face of genealogy research. That includes revising the curriculum for colleges and independent researchers, but she has the bigger picture in mind. "It's typically an older or retired person who says, let me document the family for the kids." Saxon wants younger generations to become the keepers of the family history. "Right now, it's just me and the old people in the archives…but that's going to change."

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/3029871/why-researching-our-ancestors-has-the-power-to-change-lives

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar